It took flames to engulf the French soul to remind us that cathedrals remain one of the best evangelizers, and France was once hailed as “the most Christian country.” Yet on Monday of Holy Week, the jewel of that once (and, I predict, future) Catholic country, Notre-Dame Cathedral — as central a character in Victor Hugo as Esmeralda and Quasimodo, as iconic as anything Paris added to its cityscape in the 850 years since it was constructed, and so durable that it stood fast during Robespierre’s Cult of the Supreme Being ceremonies in the French Revolution, withstood Napoleon’s emperorship, and stood tall as Nazis occupied its great city — was still yet evangelizing even as she burned, like Joan of Arc before her, like the martyrs.

She was reminding us that the world still needs the Church, because it still needs God.

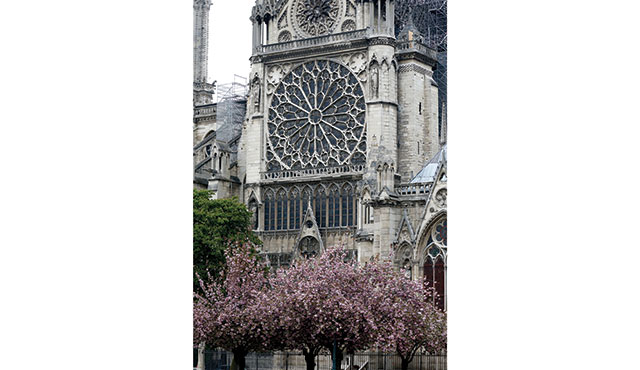

The heartbreak over the burning of Notre-Dame was felt by many, adored as it is not only by Parisian Catholics in the Archdiocese of Paris who call the cathedral home, but by admirers of varying backgrounds from around the world. They have all gazed up at Notre-Dame and shuddered at the magnificence, the breadth of human ambition and achievement, the weight of history. Until April 15, they knelt amid one of the world’s most glorious sanctuaries to honor the Real Presence of Jesus Christ.

That collective heartbreak of humanity aching over the cathedral’s shocking interior disintegration, as the spire collapsed, as the plume of smoke hovered over Paris that spring evening, suggested something metaphysical: in the week commemorating the Passion of Christ, an awareness of something precious being lost hung over Paris and beyond. Seeing the nave of Paris’s landmark in ashes we are overcome with the dreaded, all-too-human feeling that we simply cannot fully appreciate what we have until it is too late.

And, I suspect, the disturbing scene perhaps awakened something else in not a few viewers, encouraged by the stalwart stonework that survived for another day: an understanding that Notre-Dame and other sacred spaces do not exist firstly as buildings to be admired, but as portals into the sacred mysteries, into the sacramental nature of our Catholicism, with the cosmic experience of bread and wine becoming the body and blood, soul and divinity of Jesus Christ each and every day. You don’t forget that, ever — no matter how long you’ve been away.

It’s never too late to start again — not for a building, and certainly not in your heart. Like Monte Cassino after World War II, like Europe time and again, like anyone who has fallen on hard times only to get up once again, Notre-Dame will be rebuilt.

“Behold, I stand at the door and knock. If anyone hears my voice and opens the door, then I will enter his house and dine with him, and he with me” (Revelation 3:20). Jesus Christ, who is God, is endlessly persistent. Sometimes he has to rudely jolt us in order to see him, sometimes for the first time.

Cathedrals remind us of that eternal knock. They show the depth of the Catholic imagination — its rich vault of ideas, imagery, symbols, and its ability to transform even human ingenuity and ambition into tools of evangelization. It has often been remarked that the laborers of the great Gothic cathedrals, of which Notre-Dame is paramount, were anonymous. Their interest was in fulfilling the task before them. Their legacy was in the structure itself.

In his homily during the celebration of Vespers in Notre-Dame Cathedral on September 12, 2008, Pope Benedict XVI commented on not only the cathedral’s enduring witness “to the ceaseless dialogue that God wishes to establish with all men and women,” but as a place where conversions were born under its soaring vaults. Among those the pope cited was Paul Claudel (1868-1955), who at the age of 18 and a restless unbeliever, wandered into Notre-Dame on Christmas Day 1886. Claudel himself remembered it being “the gloomiest winter day and the darkest rainy afternoon over Paris.” Benedict noted it was not for reasons of faith that prompted Claudel to first enter, “but rather in order to see arguments against Christians.”

Vespers was underway. The choir was singing the Magnificat. Then everything changed for Paul Claudel. “In an instant, my heart was touched and I believed. I believed with such a strength of adherence, with such an uplifting of my entire being, with such powerful conviction, with such a certainty leaving no room for any kind of doubt, that since then all the books, all the arguments, all the incidents and accidents of a busy life have been unable to shake my faith, nor indeed to affect it in any way.”

Claudel went on to receive six nominations for the Nobel Prize in Literature over his lifetime. A 1984 New York Times article likened Claudel’s plays to those of Shakespeare and Aeschylus. Claudel himself memorialized his transformation with a poem, “December 25, 1886”:

After all, you, my Lady, made the first move.

For I was only one of those “standing around” in the sullen inattentive crowd,

One element, “standing around,” lost in the center o the trampling crowded mob,

That mass of bodies of the people under their clothes

and of flaccid hearts which held me pinned

against that pillar.

Through the beauty of Notre-Dame Cathedral and the beauty of the sacred music, the Holy Spirit entered Paul Claudel’s heart. He opened the door to greet the knocking Lord and was met by the flood of graces the Catholic Church offers. If only we open the door… are we prepared to face what lies ahead?

Now one day soon there will be new laborers transforming Notre-Dame, merging the work of those medieval builders before them, intent on preserving what cathedrals and churches stand for in a time often at odds with its message.

When the great Gothic cathedrals arose, they towered over everything else in the village, signifying that here in this place was the gateway to the divine. It was not like anything else around it. Its purpose was singular and urgent: God is here, and calling you. We are reminded of that when we see those great cathedrals still standing today — even like one of our most beloved cathedrals, somehow still dignified in its charred state. Still holy.

Let us enter their doors while we still have time, before it is too late. Only now, let us enter not as tourists but as pilgrims. No longer as laconic pedestrians, but as urgent penitents. God is here. The cathedrals still announce him to an unbelieving world, and he is calling you.

James Day is the Operations Manager at EWTN in Orange County, California.