February 2022, our times are difficult. COVID-19 and testing. Vaccines: yes or no? Shortages of all kinds, gas prices rising, inflation, on and on. Still, it helps to look at other times of distress and learn how people overcame disappointment and despair.

In 1966 and 1967, the civil rights movement was stressed and strained beyond belief. Efforts to integrate housing in Chicago were met with hatred and violence on a scale little seen in the Deep South. Yet, in September 1966, in Grenada, Mississippi, 150 black children trying to integrate schools were viciously attacked by a mob of 400. Twelve year-old Richard Sigh’s hip was broken by men hitting him with pipes.

A reporter saw “one woman draw back, cover her mouth, and repeat to no one as she watched a swirling clump of men whip a pigtailed girl, ‘How can they laugh when they’re doing it?’”

The Southern Christian Leadership Conference faced multiple difficulties from financial shortfalls to the pressures of J. Edgar Hoover’s malicious FBI and the White House.

The Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee was coming apart as leadership fights pitted those who believed in the strategy of nonviolence against voices calling for Black Power and championing retaliation.

Overall loomed the reality of the war in Vietnam. A small number burned themselves to death to protest the horror of the war. In April 1967, anti-war groups planned a huge day of Mobilization to End the War.

Would Rev. King participate? Should he? Would his speaking out against the war lose him support and financial donors? Was it wise to publicly confront President Johnson on the question of Vietnam? Would the president who had signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965†ever forgive King’s siding with those calling for an end to “Johnson’s War”?

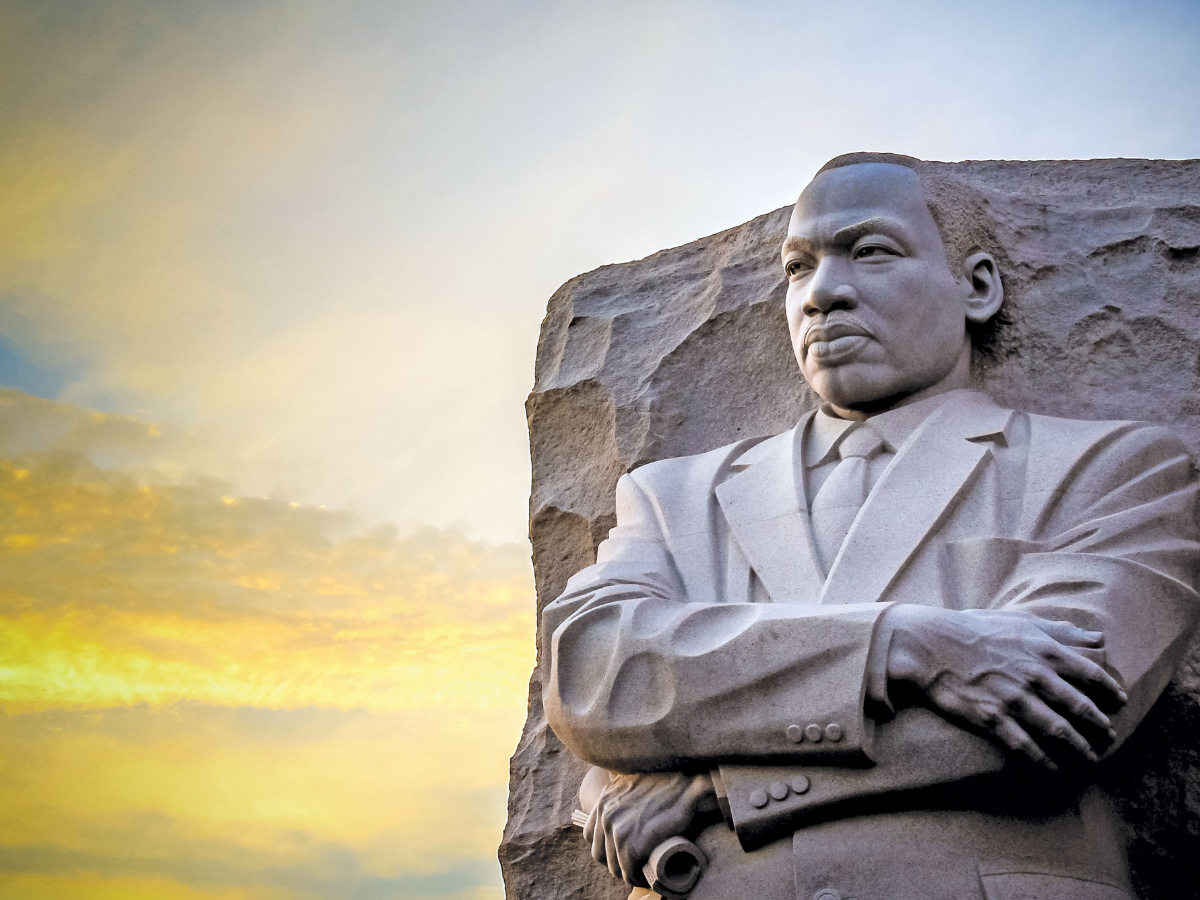

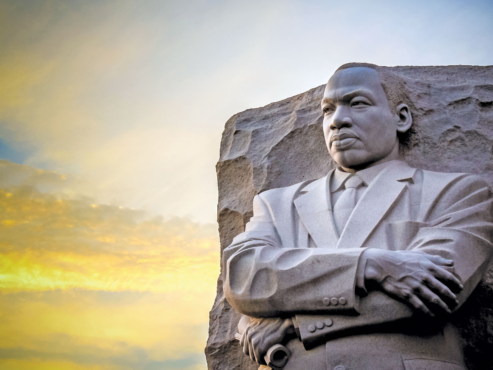

THE STATUE MEMORIAL FOR MARTIN LUTHER KING JR. IN WEST POTOMAC PARK, WASHINGTON D.C. PHOTO: SHUTTERSTOCK

During all this, King kept up a torrid pace of travel, speaking, meetings and even wrote another book, “Where Do We Go from Here? Community or Chaos.” On the eve of the anti-war demonstration in New York, King delivered one of his greatest (and least known) speeches in Riverside Church: “Beyond Vietnam. A Time to Break Silence.”

Risking much, King linked racial inequality, economic injustice and militarism as idols that Christian conscience must challenge and convert.

Kings said: “Somehow this madness must cease. We must stop now. I speak as a child of God and brother to the suffering poor of Vietnam. I speak … for the poor of America. … I speak as a citizen of the world, for the world as it stands aghast at the path we have taken.”

At the end of the speech, he sounded a clarion call to hope and solidarity:

“Now let us begin. Now let us rededicate ourselves to the long and bitter, but beautiful, struggle for a new world. This is the calling of the sons of God, and our brothers wait eagerly for our response. Shall we say the odds are too great? Shall we tell them the struggle is too hard? Will our message be that the forces of American life militate against their arrival as full men, and we send our deepest regrets? Or will there be another message — of longing, of hope, of solidarity with their yearnings, of commitment to their cause, whatever the cost? The choice is ours, and though we might prefer it otherwise, we must choose in this crucial moment of human history.”

Today, we can fail to imagine how difficult were the situations, personalities, societal dynamics and power struggles King had to navigate.

From death threats against himself, his family and his associates, to just the sheer stress and strain of traveling, writing, speaking night after night, King had enormous burdens to bear.

And bear those crosses he did, bringing us all a little closer to the resurrection of a nonviolent world, free of racisms and hatreds and wars of all kinds; a world of peace and prosperity, hope and healing, justice and joy.

(For more information on this topic, see “At Canaan’s Edge: America in the King Years, 1965-68,” by Taylor Branch