Editor’s note: This is the first in a series of articles about Michelangelo’s life and works.

Michelangelo Buonarroti was nearly 89 years old when he died in 1564. This multitalented Florentine sculptor was often put to work by popes who absolutely knew they could not let such talent go unused. As much as he did not consider himself a true one, Michelangelo was also a painter. He was a prolific poet, particularly of sonnets. His many letters preserve aspects of his personality we do not get to see in his other art; his architecture continues to define the Roman landscape today.

One of his crowning achievements, the art of the Sistine Chapel, the sacred place where conclaves elect the successor of St. Peter, is currently available in near-life-sized replicas for close inspection and contemplation on the campus of Christ Cathedral.

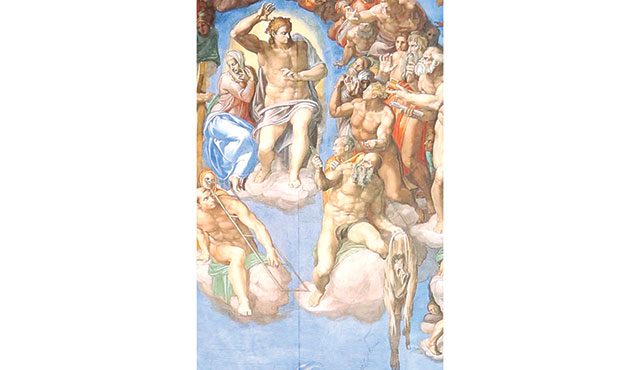

Michelangelo’s sprawling, complex, theologically brilliant Last Judgment, spanning the altar wall in the Sistine Chapel, was composed 25 years after he completed the art on the Sistine ceiling. The project took five years, with over 300 characters packed around the central figure, Christ, with some souls tormented for eternity, and others, the elect, ascending the heights of everlasting life.

So rich in detail, the layered themes of the fresco require intense meditation. When it comes to admiring the work of Michelangelo, tourist and believer blend in mutual awe.

It is well known how Michelangelo would often inject his own self-portrait into crucial scenes and crucial characters throughout his career. There is no exception in the Last Judgment.

At the center the beardless, triumphant Christ, with only the faintest of lingering scars from the lance and nails of the Crucifixion. Like most of Michelangelo’s men, Christ here is muscular and imposing: this is no passive Redeemer. In a half-circle, eager eyes are all on Him, captivated and wary, waiting for the verdict of eternal destiny. Just off Christ’s left foot is a grim, hulking figure armed with a sculptor’s file: the personage of Saint Bartholomew. And yet quite startling, while he holds the tool in his right hand, in his left he clutches his own sorry skin. It is this particular representation in which Michelangelo would add his self-portrait.

Why would the master choose such a morbid depiction to include his own likeness on one of Western culture’s towering achievements? Recall who Bartholomew is—the initially cynical Nathanael Bar Tolmay (“What good can come from Nazareth?”), who was shocked into conversion when Jesus revealed knowledge of an apparent significant moment for Nathanael that occurred to Nathanael under a fig tree. We are not sure what that particular moment was, but Nathanael was amazed Jesus knew of it. “You will see greater things than this,” Jesus promised him upon seeing Nathanael’s stunned reaction (John 1:47-50).

Church tradition has it that Bartholomew, spurred by the events of Christ’s Resurrection, Ascension, and Pentecost, eventually journeyed to Armenia where he underwent a martyr’s death—by flaying, that is, the process of having one’s skin removed. Many onlookers of the Last Judgment may not know that history of Saint Bartholomew when gazing, probably not a little disconcertingly, at the macabre depiction of the tortured figure clenching his own skin.

And yet there is great significance in Michelangelo’s decision. Georgia Illetschko in his book, “I, Michelangelo,” notes that in choosing the flayed character of Bartholomew for his self-portrait, Michelangelo was indicating his own gradual self-stripping in deference to the will of God. The artistic world is never bereft of ego, and here in the skin of Bartholomew lies a valuable lesson for artists. “[P]eeling or skinning is a painful sacrifice as well as a creative act that leads the way to new life,” Illetschko writes.

Illetschko further notes that as Michelangelo’s career advanced, the more interested he became with contemplation of the divine over the egoistic quest for personal accomplishments—even if, of course, his ego was never completely quelled. Michelangelo’s artistic interest in the transcendent would be best summarized by Italian film director Franco Zeffirelli, who discovered as he was making the celebrated miniseries Jesus of Nazareth, “[W]hen you begin to involve yourself in Godly matters it is terribly difficult to return to mundane trivialities.”

Michelangelo himself said, “Neither painting nor sculpture will be any longer to calm my soul, now turned toward that divine love that opened his arms on the cross to take us in.” Imagine today’s heralded artists undergoing such a transformation.

Michelangelo’s work is both epic and intimate. At the Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel: The Exhibition, currently on display in the Christ Cathedral Cultural Center, seating is available before various works. It is a rare chance of being close to the work, and the artist. The exhibit is also a challenge for artists today to integrate their faith with their artistic passions. “Church needs art,” Pope St. John Paul II, the former actor and poet, voiced in his Letter to Artists. “Does art need the church?