In Jesus’ time, the Jewish people believed that the living could assist the deceased if they needed to atone for their sins. “Thus he made atonement for the dead that they might be absolved from their sin.” (Macc. 12:41-46)

Jesus never told His followers to stop praying for the dead; He emphasized the unity between all people through His sacrifice on the Cross.

From the days of the apostles, those who have passed were always considered part of the body of Christ: The Church Militant (here on earth), The Church Penitent (in Purgatory) or the Church Triumphant (in Heaven).

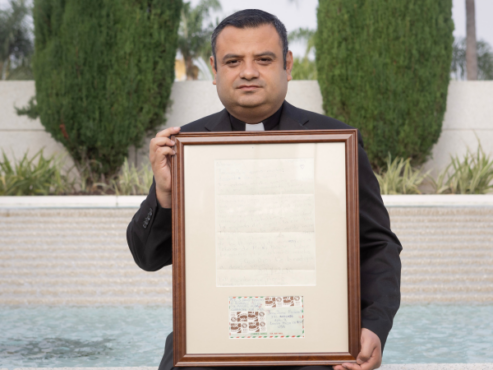

FR. DAVID MORENO HOLDS A FRAMED LETTER HE WROTE AS CHILD TO HIS LATE BROTHER JAIME. PHOTO BY DREW KELLEY/DIOCESE OF ORANGE

Many customs and observances have evolved over the centuries since Christ, often merging indigenous practices with Catholic teaching.

“The Church adopted Día de los Muertos to create a link between ancient Central American indigenous culture and Christianity, where Catholic traditions mirrored native celebrations,” said Fr. David Moreno, Parochial Vicar at Christ Cathedral.

Born and raised in Culiacán, the capital of Sinaloa in Northern Mexico, Fr. David remembers Día de los Muertos as a joyous family day beginning Nov. 1 and continuing all night until Nov. 2.

Beginning on the Solemnity of All Saints, families gather to pray for loved ones who have passed. They go to their gravesite and keep vigil all night. Far from a sad event, it is filled with joy, good food, lighthearted stories and the retelling of family history.

“We start with the Angelitos – visiting the graves of children who have died and then moving to other family members,” said Fr. David. “Sometimes, the celebration becomes a moveable feast as families go to various cemeteries to honor all the branches of their family tree.”

Fr. David recalled, “At the picnic, families build an altar with the Cross at the top because everything points to Christ. We bring photographs of loved ones, share favorite foods and tell stories. It keeps the family united with its past; when you remember the person, they are alive. We also say many prayers, including the rosary.”

He added: “Mexicans have a very positive relationship with death. Our culture is not afraid of death – not that we seek it, but it is a part of life. We believe in the communion of saints and pray for their entry into Heaven. Most importantly, death doesn’t mean one loses the connection with people they love. It gives us hope because we await the resurrection of the body.”

To people outside the culture, the images of Día de los Muertos – skeletons, skulls adorned with flowers and other macabre can be unsettling. But they are joyful and smiling to reflect a lighthearted view of death in the Central American culture.

“Skeletons with a crown of flowers symbolize life and death, said Fr. David. “We believe there is a very thin line between life and death and that our deceased loved ones are with us still.”

Fr. David was the youngest of six children and 10 years younger than his next oldest sibling. His father, Jose Moreno, was an investigative journalist and manager for El Sol de Sinaloa.

He grew up reading multiple newspapers and still has numerous news apps he checks daily.

“My dad made me read the news articles and taught me to think and read between the lines to understand what is happening around us,” said. “When I prepare a sermon, I usually go to the current news when deciding what to preach so that I can preach in a way that is more relevant to the congregation’s life. I love the smell of newsprint!”

From a small town with only a middle school education, his mother was equally aware and outspoken in civic affairs.

“As a young boy, I remember going with her to protests when she thought freedom was in danger,” Fr. David said. “She taught me to speak up. Both my parents were highly political. They taught me to love my country, freedom and democracy. I love my faith, too.”

He added: “From when I was a little boy, I knew something important was happening at Mass. As I grew older, I kept telling God to wait. I wanted an education—including an MBA— to date, and to have a career. And God allowed this. But one day, when working as a manager for Mission Bell Foods (makers of Mission Tortillas) in Tijuana, I realized that the time had come to do what God wanted.”

He entered the seminary in Mexico but completed his studies at St. John’s Seminary in Camarillo. He was ordained for the Diocese of Orange in June of this year.

The Moreno family is still tight knit. When his brother Jaime passed away in Costa Mesa from COVID, Fr. David went to his home to help remove his belongings.

“When I opened his desk drawer, right on the top was a letter I had written him when I was six years old, telling him what I wanted for Christmas. I had no idea it meant that much to him.”

His father passed away a few years ago, but Fr. David still calls his mother in Culiacán daily.

Fr. David’s father purchased a family plot in Culiacán, and he has a place there.

“I don’t know if you can really prepare for your day of death,” he said, “but I plan on dying while serving others.